SPAC Transactions: Risk of Goodwill Impairments Post de-SPAC

By Tiffany J. Westfall and Atul Singh

Access to equity capital markets is critical for companies in the high-growth phase. Special Purpose Acquisition Companies (SPACs) are publicly traded shell companies that provide a way for private companies to become public. SPACs accomplish this by finding a private target company and merging with it; this is opposed to the traditional method of a private company pursuing an initial public offering (IPO) or direct listing to access public markets.

SPACs have surged in popularity over the past five years. Waves of SPACs have risen and fallen since their inception in 1993, but the recent wave is by far the largest. In 2021, 613 SPAC IPOs raised more than $162.5 billion, which was more capital raised than all previous years combined.

As of October 2022, there have been 1,112 SPAC IPOs raising more than $300 billion in proceedsi. One benefit for private companies to utilize the SPAC vehicle as opposed to an IPO is providing access to capital even when market volatility and other conditions limit liquidity.

This article focuses on an unintended consequence that post de-SPAC companies may encounter with goodwill. Opponents of SPACs argue that the current regulatory environment leaves material gaps in offering regulation that increases risks for investors in SPAC mergers compared to IPOs. The public shareholders of SPACs have very little involvement in choosing the private target company to be acquired or its valuation. This may leave them exposed to the risk of acquiring overvalued targets, which in turn can lead to future goodwill impairments.

The article titled “Accounting for De-SPAC Transactions” was published in the September/October 2021 issue of Today’s CPA. This article should be read in conjunction with the aforementioned published article and expounds accounting implications of goodwill impairment testing in the post de-SPAC period, based on ASC 350, Intangibles – Goodwill and Other.

SPAC Formation and Funding

Generally, a SPAC is formed by an experienced management team or a sponsor with nominal invested capital, typically translating into a ~20% interest in the SPAC (commonly known as founder shares). The remaining ~80% interest is held by public shareholders through “units” offered in an IPO of the SPAC’s shares. Each unit consists of a share of common stock and a fraction of a warrant (e.g., 1/2 or 1/3 of a warrant).

Founder shares and public shares typically have similar voting rights, with the exception that founder shares usually have the sole right to elect SPAC directors. Warrant holders generally do not have voting rights and only whole warrants are exercisable.

Each SPAC starts its life by selling its shares to initial investors in its own IPO. The IPO proceeds, typically $10 per share, are escrowed in a trust account while the SPAC has 18 to 24 months to search for a private target company to take public by acquiring it in a merger, often referred to as de-SPACing. If the SPAC does not complete a merger within that 18-24 month timeframe, the SPAC liquidates and the IPO proceeds are returned to the public shareholders.

Once formed, the SPAC will typically need to solicit shareholder approval for a merger and will prepare and file a proxy statement (or a joint registration and proxy statement on Form S-4 if it intends to register new securities as part of the merger). This document will contain several matters seeking shareholder approval, including a description of the proposed merger and governance matters.

The Form S-4 also includes financial information about the target company, such as historical financial statements, management’s discussion and analysis (MD&A), and pro forma financial statements showing the effect of the merger. Once shareholders approve the SPAC merger and all regulatory matters have been cleared, the merger will close and the target company becomes a public company.

A Form 8-K, with information equivalent to what would be required in a Form 10-K filing of the target company (often referred to as the Super 8-K), must be filed with the U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) within four business days of closing. After the closing of the SPAC merger, the combined entity is a publicly traded company and is responsible for complying with ongoing Exchange Act filing requirements.

Accounting Acquirer Consideration

The accounting acquirer is the entity that has obtained control of the other entity (i.e., the acquire) and may be different from the legal acquirer in a SPAC merger. If the target company is determined to be the accounting acquirer, the transaction will be accounted for similarly to a capital raising event (i.e., a reverse capitalization).

If the SPAC is determined to be the accounting acquirer, the transaction is accounted for as a business combination in accordance with the guidance in ASC 805, Business Combinations (i.e., a forward merger). The pro forma financial information included in the Form S-4 will reflect purchase accounting applied to the target company’s assets and liabilities and will require a stepped-up to fair value valuation.

Financial Reporting Considerations – Post Reverse Recapitalization

Reverse recapitalizations do not result in a new basis of accounting and the financial statements of the combined entity represent a continuation of the financial statements of the target in many respects. However, the reverse recapitalization triggers unique accounting with respect to the entity’s equity accounts, EPS and transaction costs.

Financial Reporting Considerations – Post Forward Merger

After the SPAC merger, the historical financial statements of the predecessor become the financial statements of the combined company. The SEC staff’s guidance on the presentation of predecessor financial information is included in Section 1170.2 of the SEC’s Division of Corporation Finance’s Financial Reporting Manual.

In a forward merger (i.e., a business combination), because a SPAC generally has nominal operations before the combination, the target operating company is usually designated as the predecessor of the combined company. The application of purchase accounting to the financial statements of the target in a forward merger results in a new basis of accounting to be reflected in the successor’s financial statements after the transaction. To emphasize the change in reporting entity, the successor and predecessor periods would be separated by a black line in the standalone financial statements, similar to the presentation in the standalone financial statements of an acquiree after a business combination when pushdown accounting is applied.

The financial statement disclosures should also include traditional business combination related items, including purchase price allocation and pro forma disclosures. Typically, the combined company in forward merger transactions has goodwill balances as a result of the purchase price allocation. The goodwill balances can be significant because some de-SPAC entities have 60-80% of the purchase price recorded as goodwill.

When de-SPAC entities have a significant portion of the purchase price allocated to goodwill, one question is within a year or two years will the economic results be at a level to substantiate that amount of goodwill?

The remainder of this article focuses on de-SPAC companies accounted for as forward mergers and their annual goodwill impairment testing considerations.

Goodwill Impairment Testing – Post Forward Merger

Goodwill is an asset representing the future economic benefits arising from other assets acquired in a business combination that are not individually identified and separately recognized. In accordance with ASC 350, Intangibles – Goodwill and Other, post de-SPAC companies do not amortize goodwill. Instead, post de-SPAC companies are required to test goodwill and any other intangible assets with an indefinite life for possible impairment on an annual basis and on an interim basis if there are indicators of possible impairment (i.e., triggering events).

Goodwill is considered to be impaired when the carrying amount of the reporting unit that includes the goodwill exceeds its implied fair value. In this situation, an impairment loss is recognized for the amount that the carrying amount exceeds its fair value, up to the goodwill amount for the reporting unit.

Accounting Standards Update (ASU) No. 2017-04, Intangibles – Goodwill and Other (Topic 350): Simplifying the Test for Goodwill Impairment (ASU 2017-04), outlines the test procedures for subsequent measurement of goodwill. The goodwill impairment test is performed by comparing the fair value of the reporting units to the carrying value of the reporting units.

Public companies are required to review the stock price and overall market capitalization as part of the impairment test. An impairment charge is recorded for the amount the carrying value of the reporting unit exceeds its fair value, not to exceed the total goodwill allocated to that reporting unit.

Goodwill Control Premiums

While not required under U.S. GAAP, a publicly traded company should reconcile the fair value of its reporting units to its stock price and market capitalization to corroborate its fair value estimates used in both interim and annual impairment testing.

When the estimated fair value of a company is greater than its market capitalization, this generally implies that a control premium has been considered in determining the fair value of the company’s reporting unitsii. The SEC staff, in fact, has requested in SEC comment letters that registrants provide evidence of this analysis to justify an implied control premium.

A company’s market capitalization is considered a level 1 input (readily observable market value) under ASC 820, Fair Value Measurements.

Companies are expected to document and explain, in sufficient detail, the reasons for any significant difference between the sum of the fair values of their individual reporting units and the company’s total market capitalization. The extent of the documentation and analysis will vary based on facts and circumstances. Regardless of whether the analysis is quantitative, qualitative or some combination of those approaches, the SEC staff has said it would expect a company to have objective evidence to support the reasonableness of its implied control premium.

Although no bright lines exist in U.S. GAAP, as a general rule of thumb, control premiums less than 35-40% are typically viewed as “reasonable.” Anything above this range is at risk for SEC scrutiny.

Goodwill Impairment Triggering Events Consideration – Post Forward Merger

Once a SPAC opens on the market, the share price is usually set at $10 and can fluctuate from there. It was a volatile year for equities, with the Nasdaq down roughly 33% year to date (as of October 2022). Throughout 2022, the IPO and SPAC markets have not seen much activity.

One unintended consequence for de-SPAC companies is a rapid decline in their stock price from the typical $10 opening price in the equity markets. The $10 opening price in equity markets for de-SPAC companies is unique because the underwriters have less of an influence on the opening price than traditional IPOs.

The decline in stock prices for de-SPAC companies has caused some de-SPAC companies to analyze goodwill impairment triggering events as a result. This is most prevalent in de-SPAC companies formed through forward mergers because those de-SPAC companies often have higher goodwill balances than de-SPAC companies formed through reverse recapitalization.

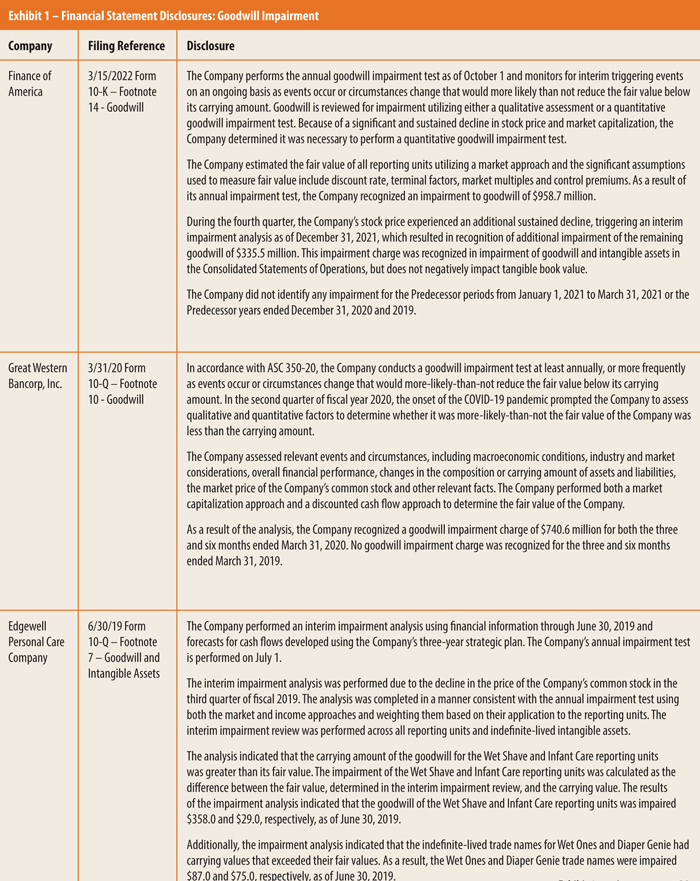

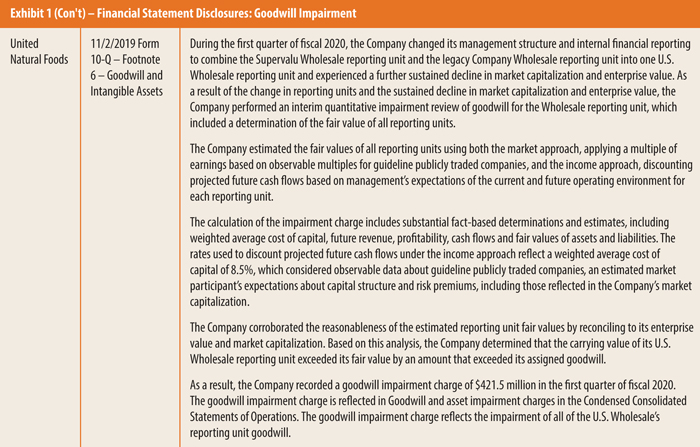

Refer to Exhibit 1 for some examples of companies’ impairment charge disclosures resulting from market capitalization and implied control premium as part of the goodwill impairment analysis. These goodwill impairment charges are significant and can equal hundreds of millions of dollars.

Companies must also consider other business implications, other than reporting it in their financial statements filed with the SEC, that result from recording impairment losses. Companies must report goodwill impairment losses in their Form 8-K earnings release for the corresponding period that the goodwill impairment charge is recorded.

The SEC permits companies to elect to disclose a material impairment earlier than the earnings release date through the filing of a Form 8-K and disclosing an Item 2.06. Goodwill impairment losses are treated as non-cash add backs to common non-GAAP measures (i.e., adjusted net income and adjusted EBITDA). Non-cash impairment losses may also impact certain debt covenants.

Finally, companies need to assess any tax impacts associated with goodwill write downs (i.e., decrease deferred tax liabilities).

There continues to be a large investment of capital in existing SPACs seeking targets and a growing number of private equity firms, venture funds and other sponsors forming SPACs.

As of October 2022, there were 100 SPACs in the IPO pipeline and 667 that had completed their IPO and were either searching for a target or have announced an acquisition.iii The newly formed de-SPAC companies may need to consider the additional time needed to prepare for the rigorous financial reporting demands of public firms. Given the recent surge in SPAC mergers and SPAC IPOs, these goodwill impairment write downs could result in broader economic consequences in the future.

About the Authors:

Tiffany J. Westfall, is an assistant professor of accounting in the Miller College of Business at Ball State University. Contact her at tjwestfall@bsu.edu.

Atul Singh is assistant professor of accounting in the Miller College of Business at Ball State University. Contact him at aksingh@bsu.edu.

Footnotes

i “US SPAC IPO Issuance” SPAC Research, https://www.spacresearch.com/

ii A control premium is typically defined as the amount or percentage by which the pro rata value of a controlling interest exceeds the pro rata value of a noncontrolling interest in a business enterprise to reflect the value of control.

iii “Active SPAC Summary” SPAC Research, https://www.spacresearch.com/