Evaluating the Modernized SEC Rules Governing Auditor Independence

By Steven Mintz, Ph.D.

On October 16, 2020, the Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) adopted amendments effective for certain rules regarding auditor independence requirements (known as Rule 2-01 of Regulation S-X). The Public Company Accounting Oversight Board (PCAOB) adopted conforming amendments on November 19, 2020, to eliminate differences and duplicative requirements that would exist between the independence requirements of the Board and the SEC. The effective date of the SEC’s 2020 amendments to Rule 2-01 was June 9, 2021.1

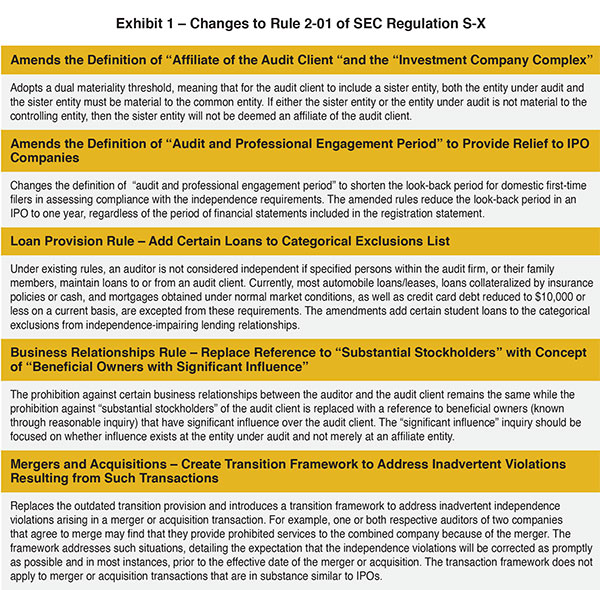

The intention behind these amendments is to modernize the SEC’s rules governing auditor independence and more effectively focus the analysis on relationships or services that may threaten an auditor’s objectivity and impartiality, as well as reduce the effect that the independence rules can have on a company’s ability to select an auditor. Exhibit 1 summarizes the primary changes in the rule.

Motivation for the Changes to Rule 2-01

In recognition of the critical importance of auditor independence to the reliability and credibility of our financial reporting system, the SEC’s auditor independence rules require auditors to be independent of their clients both “in fact and appearance.”

The amendments reflect the SEC’s experience in applying the independence requirements, particularly in certain recurring situations where specific relationships and services triggered technical independence rule violations without consequently impairing an auditor’s objectivity and impartiality.

The changes are intended to more effectively and efficiently identify transactions and relationships that could impair an auditor’s independence. The SEC believes the changes will reduce compliance costs for both audit clients and their auditors by updating unduly burdensome requirements for relationships and services that are less likely to threaten auditor objectivity and impartiality. They will also diminish the effects of technical violations of the independence rule that has no bearing on objectivity and impartiality in meeting audit obligations.

The technical complications addressed in the rule are a symptom of a long-standing problem within the auditing firms – a lack of discipline and accountability surrounding independence conflicts. The purpose of the changes to the rule is to “maintain the relevance” of the SEC’s auditor independence requirements, to “evaluate their effectiveness in light of current market conditions and industry practices,” and to “more effectively focus the independence analysis on those relationships or services that the Commission believes are most likely to threaten an auditor’s objectivity and impartiality.”2

The implication is that the rules are outdated or focused on non-essential matters, and this is true in limited cases. However, entirely ignored in the adopted rule changes is whether extensive evidence exists that audit firms’ compliance with existing standards is inadequate, that lack of compliance undermines auditors’ ability or willingness to approach the audit with professional skepticism, and that more fundamental reform is needed to strengthen the rules and increase accountability for violations. The SEC needs to keep independence on its agenda for more substantive changes.

The General Standard

Although several substantive amendments were made to the auditor independence requirements, what is known as the “general standard” (i.e., Rule 2-01(b)) did not change because of these amendments. The introductory text to Rule 2-01 indicates, in evaluating the general standard, the SEC will consider whether a relationship or service:

- Creates a mutual or conflicting interest with the audit client;

- Places the auditor in the position of auditing their own work;

- Results in the auditor acting as management or an employee of the audit client; and

- Places the auditor in a position of being an advocate for the audit client.

When applying these amended standards, companies must keep in mind the general standard, which further indicates that “an accountant is not considered to be independent with respect to an audit client, if the accountant is not, or a reasonable investor with knowledge of all relevant facts and circumstances would conclude that the accountant is not, capable of exercising objective and impartial judgment on all issues encompassed within the accountant’s engagement.”3

Therefore, even in circumstances when a service or relationship is not explicitly prohibited by the requirements under Rule 2-01, the general standard requires auditors, audit committee members, and management to evaluate a service or relationship from the perspective of a reasonable investor and determine whether there is a real or perceived impact on the auditor’s objectivity and impartiality.

Investor Interests

The capital markets depend on the steady flow of timely, comprehensive and accurate information. Auditors have a central role to play in ensuring the accuracy of their reported information. Like the SEC rules on which they are based, the modernized independence rule would weaken auditor independence standards, further undermining investors’ faith in the reliability of financial disclosures and putting the integrity of our capital markets at risk. Independence may take a back seat to objectivity and impartiality in assessing whether an auditor is independent of an audit client and management.

A persistent challenge exists because auditors are paid and supervised by the companies they audit so that investors can only trust in the reliability of those financial statements if auditors maintain their independence to the extent possible within this conflicted business model and approach the audit with an appropriate degree of professional skepticism. Oftentimes, auditors have failed to live up to this standard and investors have paid the price. In short, auditors do not always meet their gatekeeper obligation because of these conflicts, thereby placing their own interests and those of the client ahead of the public interest.

Providing Non-Audit Services and Independence

Historically, and increasingly most recently, each of the Big Four firms have been found to have provided non-audit services to audit clients that violate the independence rules of the SEC and PCAOB. Therefore, it would seem the answer is to strengthen the requirement, not weaken it by relying mostly on objectivity and impartiality.

For example, current rules prohibit an auditor from entering into preliminary or other negotiations on behalf of an audit client, by promoting the client to potential buyers, or “with respect to subsequent audits of a client of the accountant renders advice as to whether or what price a transaction should be entered into.”4

It is possible that with the modernized rules, an otherwise prohibited nonaudit service, such as providing advice and the implementation in mergers and acquisitions, would be permitted because the auditors judge that they can still be objective and impartial in providing audit services regardless of the merger and acquisition services.

Moreover, the auditor might judge that independence violations will be corrected as promptly as possible and, in most instances, prior to the effective date of the merger or acquisition thereby enabling the inadvertent violation. This seems to build a contingency factor into the determinations.

Audit Quality Controls

QC Section 20 of PCAOB standards describes the requirements for audit firms in developing and maintaining a System of Quality Control for a CPA Firm’s Accounting and Auditing Practice. However, there are no regulatory requirements for auditors and audit firms to assess their own audit quality controls and report on them like management must do under the Sarbanes-Oxley Act (SOX) regarding its internal controls over financial reporting (ICFR).

The SEC and PCAOB should require auditors and audit firms to assess their own quality controls and report on them because they are the first line of defense to ensure that those systems are operating as intended, designed to ensure audit independence, and establish mechanisms to control for relationships and services that might pose threats to an auditor’s objectivity and impartiality.

The purpose of these standards is to provide the firm with reasonable assurance that the firm and its personnel comply with relevant ethical requirements when discharging professional responsibilities. The public has a right to know whether these requirements have been met.

A review of recent PCAOB inspection reports shows, for example, that staff members routinely find deficiencies related to auditor independence, objectivity and professional skepticism, two cornerstones of an effective audit. In many cases, it was the absence of effective audit controls that enabled violations such as these to occur.

As PCAOB indicates in its October 2021 Staff Update and Preview of 2020 Inspection Observations, a review of the audit firms’ quality controls identifies deficiencies in certain firms where “the engagement quality reviewers did not maintain objectivity in performing the review, as they assumed responsibilities of an engagement team member and performed audit procedures or had served as the engagement partner during either of the two preceding audits.”

PCAOB also observed situations where identified deficiencies in inspection reports were not disclosed through an audit firm’s internal inspection procedures directed to the same engagements. This suggests that the firm’s quality control system “does not provide reasonable assurance that the audit firm’s internal inspection program is suitably designed and/or being effectively applied.”

Violations found at both the largest firms and at smaller firms have included:

- A failure to have adequate systems in place to provide investors with confidence that the audit firm was in fact complying with the independence rules and;

- The existence of evidence that auditors were misleading audit committees by failing to provide them with the information they need to make informed decisions.

The importance of having an effective system of audit quality controls in making independence determinations was made clear on April 5, 2022, when PCAOB disciplined KPMG’s former Vice Chair of Audit, Scott Marcello, for supervisory failures in connection with KPMG’s receipt and use of confidential PCAOB inspection information. PCAOB’s order found that Marcello failed reasonably to supervise KPMG personnel who engaged in a scheme to illegally obtain and use confidential PCAOB information in an attempt to improve KPMG’s PCAOB inspection results.5

Audit quality controls should serve as the backbone for making proper assessments of objectivity and impartiality to ensure they are sufficient to overcome any deficiencies in audit independence.

Using a Materiality Standard to Judge Independence

As previously mentioned, the modernized rules adopt a dual materiality threshold to assess whether a sister entity should be included as part of the audit client. If so, the independence rule would apply to both clients as if they were one entity.

One area of concern addressed in the new independence rule is that problems can arise when otherwise permissible non-audit services are provided to a non-audit client that becomes an affiliate of an audit client. The independence rules then apply to both clients as if they were one entity.

Some firms are now using a materiality criterion to determine whether these non-audit services provided to an affiliate entity, which would be prohibited if the parent had provided them, violate the independence requirement in audit engagements. Applying such a materiality standard can have the effect of dismissing otherwise improper relationships.

Using a materiality criterion to determine whether non-audit services should be allowed raises certain questions such as:

- Is independence a standard best left to the individual judgment of the auditors or should it be based on SEC regulations and PCAOB standards?

- Where should the line be drawn in making materiality determinations?

- By applying a materiality criterion to affiliate relationships, is the SEC creating an ethical slippery slope where other areas of the audit might be judged by a materiality criterion?

An example of the ethical slippery slope might be the question of whether an audit firm should be allowed to accept contingent fees in audit engagements. The current ethics rules say ‘no,’ because it might violate the general standard. However, if the non-audit services are not material, would it then be acceptable to accept such forms of payment when auditing the client so long as objectivity and impartiality can be maintained?

Recommendations

1. The SEC and PCAOB should require auditors and audit firms to assess their own quality controls and report on them to the public to ensure that those systems are operating as intended, designed to ensure audit independence, and establish mechanisms to control for relationships and services that might pose threats to an auditor’s objectivity and impartiality.

2. PCAOB should no longer allow audit firms to have one year to fix problems with their audit quality controls before these deficiencies are made public. Investors have a right to know about the deficiencies and make their own judgment on the quality of audit work in a timely manner. This would enhance assessments whether objectivity and impartiality have been maintained even if there are technical violations of independence.

3. The SEC should provide guidance to auditors (and the public) about how the materiality standard should be applied through a “Question and Answer” document.

It is troubling that the SEC may have given up in its efforts to make independence the cornerstone of audit engagements; instead, it may be over-relying on objectivity and impartiality under the guise of a materiality exception.

Moreover, subjective determinations of objectivity and impartiality have been elevated to a position that might enable an auditor or audit firm to engage in relationships or services that may threaten independence but still be allowed because objectivity and impartiality can be maintained in the judgment of the auditor.

About the Author:

Steven Mintz, Ph.D., is a Professor Emeritus from the California Polytechnic State University in San Luis Obispo, California. Contact: smintz@calpoly.edu.

Endnotes

2 https://www.sec.gov/news/press-release/2020-261

3 https://www.sec.gov/rules/final/2020/33-10876.pdf.

4 https://www.sec.gov/rules/final/33-7919.htm.

5 https://www.jdsupra.com/legalnews/the-pcaob-brings-first-failure-to-5499230/.

Related CPE:

Navigating the Gray: An Advanced Guide to Auditor Independence Compliance