Hindsight is 20/20

FEATURE

An Investigation Into the Causes and Impact of the Incredible Fraud and Collapse of Wirecard

By Madeline Trimble, Ph.D.; Yi Ren, Ph.D., CPA; and Jomo Sankara, Ph.D., ACMA, CGMA

The implosion of the German fintech giant, Wirecard AG, in the summer of 2020 is arguably one of the biggest global accounting scandals to date. The scandal raised questions about how Wirecard was able to defraud investors, analysts and regulators, and about the effectiveness of their corporate governance, enforcement bodies and auditors.

To address these questions, the authors explore the unique pressures and opportunities for fraud that Wirecard faced. Regarding the former, according to the agency theory of overvalued equity, first espoused by Michael C. Jensen in 2005, severe overvaluation is arguably a fraud risk factor, which is likely to lead to accounting scandals.1 Although this risk is omnipresent, it naturally increases amid recent concerns over whether stocks are overvalued.2, 3

Regarding the latter, the risk of overvaluation and fraud is especially prominent in complex and new industries such as the financial technology industry (fintech), which facilitates online payment collection and processing. Firms in this emerging industry may have high fraud risk as these companies are in high demand and face competition from cryptocurrencies, such as Bitcoin. Additionally, their mold-breaking models provide challenges for regulators and create loopholes for miscommunication.

In this article, the authors provide an overview of the Wirecard scandal, investigate the tools used to conduct their accounting manipulation and environments that helped contribute to their fraud, explore the connection to accounting theory, and discuss the short-term and long-term outcomes and implications of the scandal.

Overview of the Scandal

Today, Wirecard is infamous for allegedly committing one of the most astounding fraud cases in recent global business history; however, the company had rather humble beginnings. Founded in 1999 outside of Munich, Germany as a payment processor, Wirecard purchased a bank in 2006 and transformed into a full-service payment operator with services all over the globe. Their role as a payment processing service included processing digital credit purchases for global online retailers. What followed was more than a decade of success where the company’s share price increased exponentially.

Wirecard was a high growth fintech and part of Germany’s growing financial technology center. Their electronic payment processing was a step towards a cashless society and more advanced e-commerce. They differentiated themselves by advertising more advanced payment technologies than competitors.

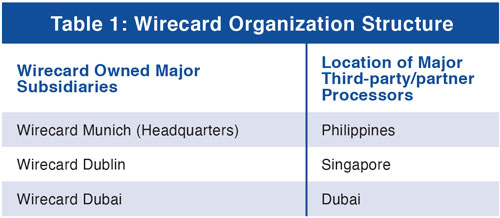

While headquartered in Germany, they conducted major processing operations in Dublin and Dubai. Their astonishing growth was due to the acquisition of small payment companies in new markets where they did not have licenses to operate. As such, their business model includes using third parties, specifically in Asia such as in Dubai, the Philippines and Singapore, to process transactions and to pay Wirecard’s commission via an escrow account.

Wirecard reached great heights by bringing the Chinese payment app, WeChat Pay, to European retailers in 2017 and teamed up with FedEx, providing FedEx customers with pickup and drop-off services in 2018. Also, major clients like Ikea, Singapore Airlines, Allianz, Aldi, and KLM lent credibility to the company. Subsequently, Wirecard earned its claim to fame as the market leader in digitizing money in Asian markets such as the Philippines, Hong Kong, Indonesia, Malaysia and India.

What makes Wirecard unique is that their fraud was not localized. Instead, they defrauded through multiple areas of the business using elaborate and complex tactics that explain, in part, the delay in the discovery of the fraud.

Next, we'll explore their toolbox for committing fraud.

Investigation Into Wirecard’s Tools for Manipulation

Wirecard was successful in misleading investors and regulators by using multiple tools for manipulation. Some tools such as inflating and advantageously timing revenues are common practice among fraudsters, but others are more unique to the current environment and Wirecard’s relatively new and underregulated industry.

Fictitious Revenue in Opaque Environments

The majority of Wirecard’s revenues were from 300,000 small customers in countries where online payment processing was unregulated and unlicensed. In these environments, reporting transparency and auditing were not required. It is estimated that nearly one-third of revenue and 80% of profits were faked.4

A main player in their deception was Dubai intermediary, Al Alam Solutions. Al Alam was a third-party processor that helped retailers accept credit through (exposed to be bogus) licenses with Visa and Mastercard. Al Alam Solutions was funneled through two Wirecard subsidiaries: CardSystems (a one-man operation in Burj Khalifa, Dubai) and Wirecard UK/Ireland. Both locations are considered tech havens. The former had no legal requirement for audits and the latter was exempt from filing in Ireland.

Al Alam had less than 10 employees, yet Wirecard purportedly moved €350m of payments from 34 key clients through this processor each month in 2016 and 2017. The use of a third-party in this case could have been a red flag since Wirecard had its own processing center (Wirecard Processing) near Dubai. Ultimately, it was uncovered by KPMG’s special audit that most of these transactions that Al Alam claimed to process for customers in Ireland, the United States and the Philippines did not take place.5

Weak Internal Controls and Corporate Governance

Much of the fraud was orchestrated by top management, or the “tone from the top,” mainly attributable to the CEO Markus Braun and COO Jan Marsalek. Palmer, Holmes and Perrewe claim that certain CEO personality traits, such as narcissism, Machiavellianism and psychopathy, can have a rippling effect throughout the C-suite.6 Specifically, this can lead to a low-quality exchange of information among executives that negatively affects leadership throughout the chain of command. This results in subordinates being retaliatory or counterproductive in their behavior, causing the quality of company outputs to suffer.

As an example, part of Braun and Marsalek’s organizational design dictated that those in assurance and risk could only verify transactions for their assigned region. Only a few senior managers were presented with global internal data of the company.

Additionally, executives failed to report known accounting irregularities to regulators in Singapore, Hong Kong and Germany, as required. Further investigation into the Asia-Pacific irregularities under Marsalek found an alleged conflict of interest. Marsalek allegedly had partial ownership of a Singapore-based third party, Matrimonial Global, which was used to move money and falsify sales in the area.

Furthermore, Edo Kurniawan, who was the head of international finance of the Singapore office and directly worked with Marsalek, was also investigated for fraud, forgery and money laundering.

Related party transactions were also an issue. For example, Wirecard paid €340m to acquire Indian processor, Hermes, from EMIF (a company of which Marsalek owned a stake), despite EMIF only recently purchasing Hermes for a mere €40m.7

Round Tripping

Wirecard commonly engaged in a tactic called “round tripping” to move money around within the entity to show favorable positions required by licensing authorities and lenders in different markets. We illustrate Wirecard’s round tripping in Figure 1.

Overstated Intangibles

Growth was essential, which helped gain the necessary attention to attract more investors. Their growth came from buying small payment processing companies and portfolios of customers (customer relationships) in new markets. Often these were overly complex, expensive foreign acquisitions that were challenging for analysts and investors to vet.

On the balance sheet, their intangible assets and goodwill balances grew demonstrably from 2005 to 2019. To keep their asset growth, Wirecard was exposed in emails as falsifying their gross profits to avoid impairment testing from auditors. As long as their acquisitions’ gross profits were greater than their annual depreciation, no impairment test was necessary.8

Falsification of Evidence

To raise capital and meet performance targets, Wirecard falsified contracts and emails about technology deals and customer contracts to inflate figures (e.g., Flexi Flex in Malaysia where an estimated €4m in revenue were falsified).9

However, potentially most egregious of their frauds was falsifying of in-person evidence gathering, which alluded EY. The two Philippine banks that were alleged to house the growing escrow accounts, BDO Unibank and Bank of the Philippine Islands, were seemingly unaware of their business with Wirecard and the onsite visits conducted.

The visits from Wirecard and EY were unauthorized except by juniors without authority to permit these engagements. These juniors were also found to have forged invoices. For example, R. Shanmugaratnam, a Singaporean associate, was arrested in December 2020 in connection with falsifying letters assuring the existence of nearly €1.2b in these escrow accounts.10

Connections to Theory

The fall of Wirecard illustrates the alarming danger of severely overvalued equity. Their stock price increased more than five-fold in two years before the fallout. Similarly, their P/E ratio increased more than 300% from 17.61 in December 31, 2018 to 76.58 in September 26, 2018. To justify the high stock price, Wirecard was likely forced into manipulative accounting practices, such as falsifying revenue discussed above.

Braun also had personal incentives to maintain an overvalued stock price. The CEO owned about 7% of the company’s shares mainly through margin loans. The shares were reportedly used as collateral for the share purchases. Consequently, if Wirecard AG’s share price declined, Braun would need to sell shares to meet margin calls. However, the effect of a CEO selling the company’s shares could alarm shareholders and create a spiral of reducing share prices. Effectively, Braun had incentives to maintain the stock price at any cost, to secure his net worth.11

As argued by Martin and Kemper in 2015 regarding the 2007 stock overvaluation that triggered a meltdown in the financial system, the overvaluation trap is an almost inevitable consequence when capital markets overvalue a company’s equity.12 However, Jensen’s warning about the massive destruction of corporate and social value due to excessive overvaluation13 has seemingly not deterred fraudulent behaviors.

For example, Carillion, the UK’s second-largest construction company, collapsed in 2018 over its aggressive accounting policies, including overstated profits and concealed debts.14 Another UK company, Patisserie Valerie, also collapsed in 2018 over its accounting fraud. In 2020, accounting fraud brought down Luckin Coffee, a Chinese company that was delisted from Nasdaq over its $310m fabricated sales.

Growth Pressures Leading to Acquisitions

To meet growth expectations, Wirecard expanded its business through value-destroying acquisitions and takeovers with a total cost of more than €1.3b between 2007 and 2017. For example, its acquisition of AllScore Payment Services for €109.3m in 2019 raised questions according to a Bernstein trader. It was estimated that Wirecard AG paid a much higher valuation ratio, nearly 24 times its EBIDTA, than normal for the small, unknown Beijing-based company.15

Academic researchers argue that overvalued companies have an opportunistic reason for stock market-driven acquisitions because the acquirers could preserve some of the inflated value by exchanging their stocks for less overvalued assets or securities.16

These growth pressures are especially pertinent to industries such as the fintech industry. For example, Kwon, Yin and Han find that high-tech firms, which would include Wirecard, show greater levels of earnings management than low-tech firms.17

Environmental Opportunities: Impact of External Monitors

The collapse called into question the role that managers, market analysts, auditors and supervisory authorities (such as BaFin) potentially had in spreading misinformation leading to Wirecard's overvaluation and eventual collapse. The latest wave of global accounting scandals has again brought up a concern regarding external monitors. For example, Commerzbank fired its former Wirecard analyst, Heike Pauls, for disclosing private information.

Although there were a few exceptions, Heike Pauls and most financial analysts were bullish about Wirecard until the disclosure of fraud and its insolvency in summer 2020.18 Similarly, supervisory authorities, such as Germany’s BaFin, have come under heavy criticism for their role in this scandal, leading to calls for more reform, more accountability and a serious overhaul of BaFin’s culture.19

Short sellers did raise the alarm; however, they were penalized by BaFin for their activity against the company. BaFin banned investors from short-selling shares in early 2018 and defended its action, claiming they were worried about how volatility would affect the stability and confidence of the German market.

According to the agency theory of overvalued equity, the risk of fraud is especially prominent in complex and new industries such as the fintech industry. Fintech companies that are facilitating online payment collection and processing may have high fraud risk, as these companies are in high demand and competition.

Following 2008, while the banking industry recovered, many major tech corporations, such as Amazon, Apple and Google, expanded to include financial payment services. However, these operations remained largely unregulated as most banking regulations only apply when greater than 50% of operations are associated with banking activities. In a study by the European Banking Authority, nearly 31% of fintech firms were completely unregulated.20

Due to the newness of this industry, regulators were unsure how to assess these blended operations. By looking at the finance and technology divisions separately, they were accused of missing the “big picture” of the company and, thus, the apparent fraud. Also, Wirecard was established in Europe and specifically Germany, which has been slow to adapt to electronic payments. As such, their payment processing market was even newer, with less oversight, than in other parts of the world.

Furthermore, investors, creditors and analysts were similarly mystified by the new industry, which potentially contributed to Wirecard’s mispricing and overvaluation.

Outcomes: Costs of Fraud and Other Consequences

The Wirecard fraud resulted in severe personal, corporate and investor losses. Regarding investors, on August 27, 2018, Wirecard shares were valued at €193.1 ($225.5)21 with a market capitalization of about €23.86b ($27.87b). As a result of whistleblower accounts and investigations from bodies such as the UK’s Financial Times, Wirecard’s share price began its decline in September 2018.

After KPMG’s audit report on April 28, 2020, Wirecard’s shares began to crash, resulting in a share price of €2.88 ($3.24) on June 29 and €0.31 ($0.38) on December 28. Overall, investors lost about €23.82b ($27.82b), approximately 99.84% of its 2018 value, as a result of the fraud.

Cost to Wirecard Management

The company’s management also incurred severe penalties due to the fraud. In particular, Marcus Braun, the former chief executive, suffered immensely both financially and by being incarcerated for his alleged involvement in the fraud.

On June 19, 2020, he resigned and on June 22, he was arrested for accounting fraud and market manipulation. He was released on $5.7m bail the following day.

However, he was rearrested on July 22, along with two other Wirecard executives, for “commercial gang fraud and market manipulation.”22 Specifically, they are accused of defrauding investors and German and Japanese banks of €3.2 billion ($3.7b) over the previous five years.23

Strengthening and Restructuring of the Regulator in Germany

Another consequence of the fraud is the reexamination of accounting regulations and audit firms in Germany. BaFin, the Federal Financial Supervisory Authority, has been sued by Wirecard’s investors. The claimants argue BaFin was negligent by ignoring evidence of the accounting scandal, resulting in the company’s collapse.24 In addition, the EU’s financial oversight body is to be turned into a European Securities and Exchange Commission with greater powers to require information from listed companies.

To strengthen future regulation, BaFin has also received a broader mandate, allowing it to carry out special audits, launch forensic investigations and increase the right to access information from third parties. Thus, it will have greater enforcement powers. Previously, BaFin had to wait for confirmation from the Financial Reporting Enforcement Panel (FREP) before it could, for example, launch a forensic audit.25

BaFin has already started to be more aggressive following the scandal and failure. For example, in September 2020, BaFin investigated Grenke AG, a leasing company, for manipulating prices of their securities, engaging in money laundering and lacking internal controls. They were using an aggressive acquisition strategy to mask low levels or non-existent cash.

In addition, the DAX, the German blue-chip stock market index, will add new quality controls by 2022. These controls will include requiring quarterly reports, audits for annual reports and instituting audit committees for supervisory boards. The DAX pledges to quickly delist those who do not meet specific criteria in a timely manner.

Impact on Ernst & Young, the Auditor

Concerning audit firms, APAS, the body that oversees auditing firms in Germany, will get new power to impose tougher sanctions on audit firms. Furthermore, German companies will be obliged to change auditors every 10 years.

Wirecard’s main auditor, EY, also faces specific consequences as a result of the failure. It was announced that Andreas Loetscher, who was EY’s chief auditor of Wirecard from 2015 to 2017, and Martin Dahmen, who succeeded Loetscher in the role, were being investigated by the German authorities.26

Additionally, KfW, the third-largest bank in Germany, and DWS, Deutsche Bank's asset management division, announced that they are considering changing auditors due to EY’s failure.

A Costly Failure Due to Large-scale Financial Fraud

The fall of the German fintech giant Wirecard led many to wonder how accounting fraud of this magnitude was orchestrated and collaborated. The case reveals how a severely overvalued company can result in fraudulent behavior and a global financial scandal.

Wirecard AG represents one of the costliest failures due to financial fraud to date. As part of the growing fintech industry, the company used many tools, such as round tripping and manipulating intangibles, to perpetuate and prolong the fraud. These tools create challenges for auditors and regulators.

The new business processes together with the pressures of overvaluation arguably created the opportunities and pressures for the fraud. Similar to other cases involving severely overvalued companies, this German success story ended in tragedy for several stakeholders, including shareholders, directors and individual auditors. However, the authors also observed some changes made after the scandal that may improve compliance oversight, enhance law enforcement and provide more protection to investors.

As the fallout from this accounting scandal continues to play out, it is important for corporate executives and investors, as well as the accounting profession and regulators, to be attuned to the fraud risk factor of severely overvalued equity.

About the Authors: Madeline Trimble, Ph.D., is Assistant Professor at Illinois State University. Yi Ren, Ph.D., CPA, is Associate Professor at Illinois State University. Jomo Sankara, Ph.D., ACMA, CGMA, is Associate Professor at Illinois State University.

Endnotes:

1, 13 Jensen, M. C., “Agency costs of overvalued equity.” Financial Management, 34, no. 1 (2005).

2 Chang, Ellen. “Are fintech company valuations too high?” Finledger, December 3, 2020.

3 Samson, A., “Investors increasingly unsettled by ‘overvalued’ markets,” Financial Times, August 18, 2020.

4 Perry, L., K. Ramanna, and B. McLean, “The Wirecard Saga,” The University of Chicago Booth School of Business, October 15, 2020.

5 McCrum, D., “Wirecard’s suspected accounting practices revealed.” Financial Times, October 15, 2019.

6 Palmer, J. C., R. M. Holmes Jr., and P. L. Perrewe, “The Cascading Effects of CEO Dark Triad Personality on Subordinate Behavior and Firm Performance: A Multilevel Theoretical Model.” Group & Organization Management, 45, no. 2 (2020).

7,9 McCrum, D. and S. Palma, “Wirecard: inside an accounting scandal.” Financial Times, February 7, 2019.

8 McCrum, D., “The Wirecard Documents, Explained.” Financial Times, October 15, 2019.

10 Chanjaroen, C., “Singapore Man Gets More Charges in $1.5 Billion Wirecard Fraud.” Bloomberg, December 7, 2020.

11 Kelly, J., “Wirecard’s Former Billionaire CEO Markus Braun Arrested Over Allegations of Fraud.” Forbes, June 23, 2020.

12 Martin, R. L. and Kemper, A., “The Overvaluation Trap.” Harvard Business Review, (2015 Issue).

14 Sweet, R., “Accounting ‘tricks’: how Carillion duped the market,” Global Construction Review, May 16, 2018.

15 Storbeck, O., “Wirecard buys Chinese payments group for up to €109m.” Financial Times, November 5, 2019.

16 Ang, J. S., and Y. Cheng. “Direct evidence on the market-driven acquisition theory.” Journal of Financial Research 29, no. 2 (2006).

17 Kwon, S. S., Q. J. Yin, and J. Han, “The effect of differential accounting conservatism on the 'over-valuation' of high-tech firms relative to low-tech firms.” Review of Quantitative Finance and Accounting 27, no. 2 (2006).

18 Storbeck, O., “Commerzbank fires its former Wirecard analyst.” Financial Times, February 2, 2021.

19 Laurent, L., “Germany’s BaFin has run out of Wirecard excuses.” The Washington Post, September 3, 2019.

20 Comfort, Nicholas and Drozdiak, Natalia, “Wirecard Flourished in Regulatory Blind Spot That’s Growing.” Bloomberg, July 7, 2020.

21 We used exchange rate data from Investing.com for all exchange rate conversions.

22 Dalder, M., “Gang fraud: New arrest warrant against ex-Wirecard boss Markus Braun.” Reuters, July 22, 2020.

23 Nagarajan, S., “Former Wirecard CEO Markus Braun was arrested for a 2nd time in relation to the company’s $2 billion accounting scandal.” Business Insider, July 23, 2020.

24 Matussek, K., “Wirecard Investors Sue BaFin Over Failure to Spot Scandal.” Bloomberg News, July 24, 2020.

25 Kimathi, S., “BaFin gets 'sovereign powers' after Wirecard scandal.” Fintech Futures, July 28, 2020.

26 Miller, H. and K. Matussek, “Ernst and Young probed by German prosecutors over Wirecard.” Bloomberg, December 4, 2020.